By Sheryl Scarborough

By Sheryl Scarborough

If the writer’s closet of useful tools could be likened to Carrie Bradshaw’s fabu walk-in, masterful accessories such as simile and metaphor would equate to exquisite Louboutin’s and Jimmy Choo’s footwear… exotic word choices would sparkle like Tiffany’s finest… and you would most likely find three-act structure in the drawer labeled: Spanx!

This is my way of saying Three-Act Structure may not be sexy, but once you try it, you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it. What exactly can Three-act structure do for you? I’m glad you asked.

- Simply organizing the main points of your manuscript into a structured beginning, middle and end will give you a comfortably shaped body of character, narrative and pace. (Spanx, baby!)

- Three-act structure streamlines the creative process, allowing you to focus on great dialog and important story points, not the organization of them. (When you’re busy being brilliant who wants to organize?)

- Which part of your story belongs in each act can be defined in enough detail that, once you learn it, you will never forget it. (Can you just give me the crib version? Yes. Read on!)

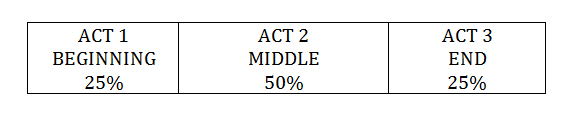

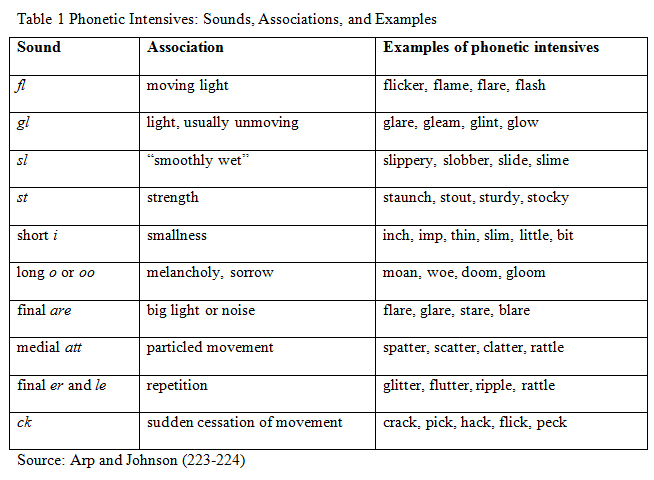

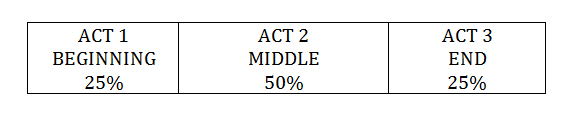

There are plenty of whole books, which define Three-Act structure and demonstrate how it works. For the purpose of this blog I’m just going to give you the basics. Three-Act structure is a specific way to balance and pace your story. The breakdown is simple:

Each Act encompasses a certain number of pages. This is the pacing part. Each act also plays a specific role in telling your story. This is the structure part.

In Act 1 the purpose is to introduce your characters and orient your reader to the setting and world you imagine.

Act 2 is where your story develops; this explains why it’s twice as long as Act 1 and Act 3.

Act 3 should be reserved for the exciting climax and conclusion of your story.

Act 1: Think of a Knight on a Quest…

Act 1 should answer WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE… but not why. It should install your character in his world in a way that quickly orients your reader. Use Act 1 to identify your main character’s problems and introduce us to his friends and foes. Establish his goals and make us care about him.

If you’ve done your job, Act 1 is when your reader develops empathy with your main character. You need for this to happen… don’t blow it. The transition at the end of Act 1 is the point where your character commits to a course of action and your reader settles into her chair and thinks, “okay, here we go.”

Act 2: Facing the Two-Headed Dragon…

If Act 1 is a Quest, then Act 2 is a series of challenges… sort of like facing a two-headed dragon! In Act 1 your reader has learned WHO, WHAT, WHEN and WHERE. By the time she reaches Act 2 she wants to know WHY.

In Act-1 your job was to establish your character’s goal.

In Act 2.1, your job is to play keep away with that goal.

Just like in real life, adversity creates character. The goal of the first half of Act 2 is to throw a series of try/fail obstacles into your character’s path. With each test your character’s commitment becomes apparant. Each time he fails, you deepen his character and reveal more about him… this is how readers find out what he wants and needs and especially how invested he is in his goal.

Not only will your character come alive through these challenges, but as you raise the stakes your reader will become more involved, intrigued and invested in your story.

The length of the trial and error portion of your story is dictated by Three-Act structure. In the first half of Act 2 you are writing toward the mid-point, which is a mere 25% of your total story.

The Mid-point: It Changes Everything…

The Mid-point can be a down moment – the catastrophic end of your character’s goal. Or, it can be an up moment – a moment of shaky success that’s so tenuous and delicate your reader will be worried that this is just one more thing for the main character to lose.

Just remember, the purpose of the Mid-point is that it changes everything.

The Second Half of Act 2: Rebuild the Character’s Goal…

Depending on your Mid-point you have either destroyed your main character’s goal or you have pushed it to such a pinnacle that it is in jeopardy. In either case, the second half of Act 2 asks “now what” or “what now.” This is where you begin to rebuild your main character’s goal. To keep the reader intrigued you must keep the pressure on your main character. Achieving his goals should be hard and take real grit and determination. This is what keeps a reader in their seat.

You also want to begin to bring your storylines together in the last half of Act 2 so that you won’t crowd the climax and conclusion of your story with loose ends.

The End of Act 2: Your Character’s Darkest Moment

Pull out all the stops and really make this moment count. This is the low point your reader has been worried about for your entire novel. And now you must give it to them. Slam your story down on your main character with all the brutality you can muster and I guarantee your reader won’t be able to stop reading.

If you have built your story to this moment, the hopes and dreams that your reader has for your main character will carry them over the end of Act 2 and straight into the climax and conclusion. They won’t be able to put down your book.

Act 3: The Unexpected and Long-Anticipated…

“Act 3 begins with the unexpected and ends with the long-anticipated.“

Author, Ridley Pearson

What this means, is as you conclude your story, you want to make the ending as exciting and unexpected as possible… and yet you want to fulfill your promise to the reader and wrap up the story they expected you would tell. In most cases, your main character will achieve a satisfying goal – maybe not the goal he started out with, but one the reader will accept as a good conclusion to your story.

Example: staying with my Knight on a Quest theme, the end of my story should involve rescuing the Princess – or in my case – The Prince.

But don’t forget to keep an element of surprise… your reader will be working with you to create a successful conclusion to your story.

My surprise that my Knight was really my Princess will be all the more delicious to my reader.

Three-Act structure is writing with purpose!

For more information, check out some of these books that do a good job explaining Three-Act structure:

King, Vicki. How to Write a Movie in 21 Days. HarperCollins Publishers, 1993. Print.

McKee, Robert. Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks, 1997. Print.

Schmidt, Victoria. Story Structure Architect. Cincinnati, Ohio: Writer’s Digest;, 2005. Kindle Edition.

Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat!: the Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Studio City, CA: M. Wiese Productions, 2005. Kindle edition.

Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers. 3rd ed. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2007. Print.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Sheryl Scarborough learned Three-Act structure during her 20 year stint as an Award-winning writer for children’s television. Now, a recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA program in writing for children and young adults, Sheryl has turned her creative attention on writing young adult mystery/thrillers.

Follow Sheryl on Twitter: @scarabs

Read more by Sheryl on her blog: Sheryl Scarborough Blog

The blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Series.

I want to thank all my fellow Dystropians for submitting their awesome blog posts this month! Each post shared great insight, sparked fun conversations, and contributed to the general awesomeness of the kidlit writing community!

I want to thank all my fellow Dystropians for submitting their awesome blog posts this month! Each post shared great insight, sparked fun conversations, and contributed to the general awesomeness of the kidlit writing community!