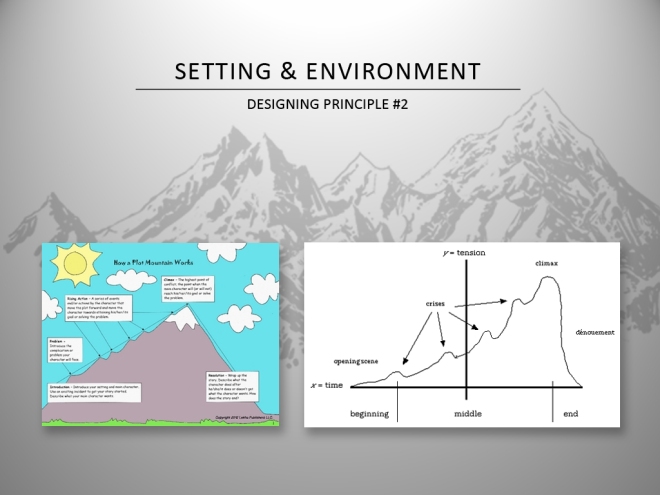

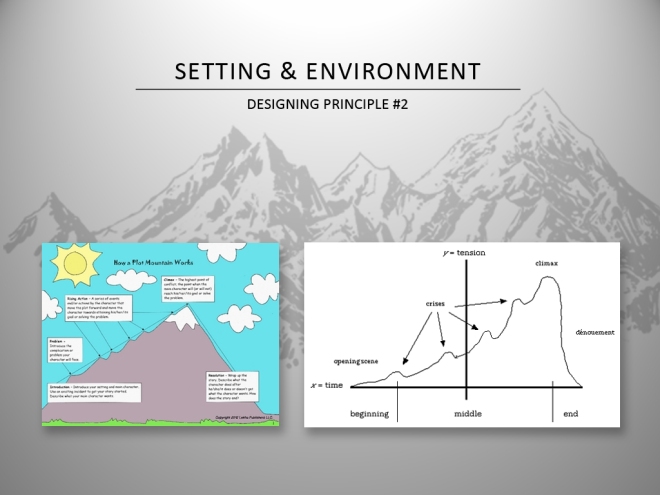

My second category in my series on designing principle is using your setting and environment to as inspiration for your story’s design.

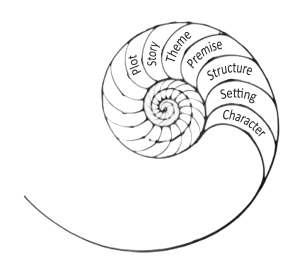

It’s interesting that the predominant structure we talk about is a mountain, which is ultimately a metaphor for a certain kind of movement and escalating energy to a story. In my first post on designing principle I mentioned the river as structure for the Heart of Darkness. Huck Finn is another example of river design and it’s worth noting that both novels have a different rhythm than the mountain structure. They meander more, they’re quieter, they reflect the inherent structure that exists in the novel’s setting.

Let’s consider other environments.

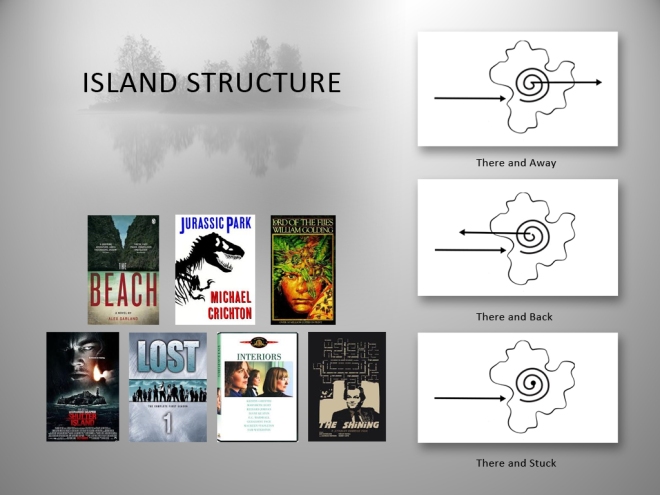

For example: Island Structure.

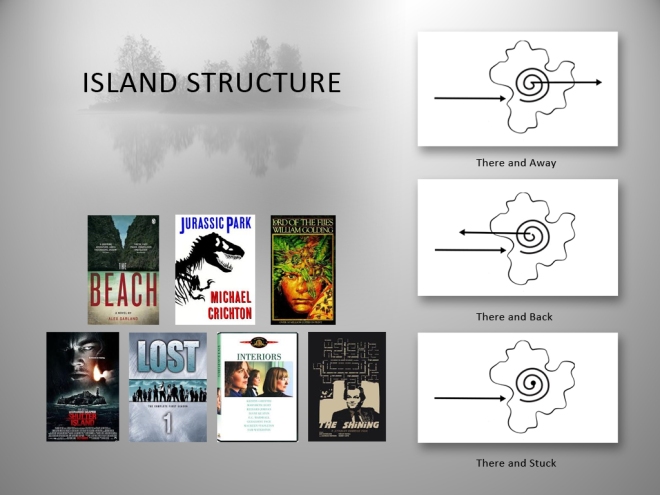

The initial energy is getting to the island, but once you’ve arrived there is an intense spinning in circles like being lost in a labyrinth. There is a desire to leave the island, but the island won’t let you go. It develops its own rules. In Shutter Island, the island becomes a metaphor for insanity. In Jurassic Park man becomes the rat in a maze of his own experiments. New rules and societies come to exist, as in The Beach, Lord of the Flies, and the TV show Lost. The overall energy is an isolated churning with no way out.

Haunted house stories have a similar structure where the house is the island – or prison – with its own rules, like in The Shining, or The House on Haunted Hill, or even Woody Allen’s dramatic film Interiors where the house is an emotional island isolating its characters.

What about the Ocean?

It has two levels: the surface and the deep. Diving underwater has a different energy than climbing a mountain; the descent becomes increasingly claustrophobic as you get closer to drowning. Whereas the surface is vast and isolating, you can go in any direction, but you must face the wildness of the waves, and the threat of the deep like in Moby Dick and The Perfect Storm.

How about the Forest?

It can be place where you get lost or find magic. In Martine Leavitt’s Keturah and Lord Death the forest becomes an important design element. The forest is death’s realm and the town is the land of the living. The forest’s edge is line upon which Keturah must dance. Initially Keturah is about to die in the forest, but Death gives her a second chance, allowing her to return home. But she’s given tasks and must come back to the forest and revisit Death, creating touch-points in the structure of the story. The story’s rhythm is this undulation between the pull of death and the desire for life.

Think about the environment of your book and ask yourself:

- Does the environment of your book have metaphorical meaning?

- How do your character’s move within it?

- Is it a prison, a path, a portal?

- What natural movement does the environment already provide for your story?

Your story may not be a mountain escalation, but the mountain also provides another good lesson, because you don’t have to be on a mountain to use mountain structure. Look at your environment to see how it might parallel another that you can use an access point to your design.

Up Next: Designing Principle #3 – Time

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!