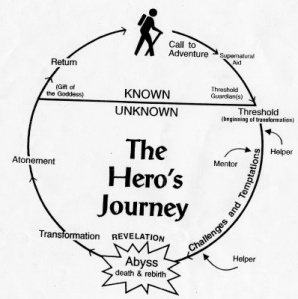

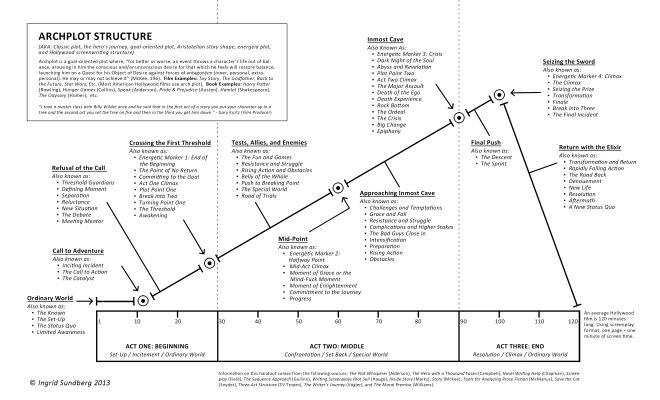

Last week I started off my Organic Architecture series by outlining the eleven major story-beats of classical design. Before I jump into alternative structures and plots I want to make sure we understand arch plot as more than just a template for story. I want to show how this story-frame can be used, and used well.

Today I’m going to breakdown the major beats of classical design using Pixar’s film Toy Story. This film is an excellent example of how arch plot can create a satisfying story experience that moves like a well-oiled machine and every piece has a purpose. Let’s take a look at how the eleven steps outlined in my previous post are put into practice.

ACT ONE:

1) Ordinary World

In the first images of Toy Story we’re introduced to Andy and his favorite toy Sheriff Woody (our protagonist). In the first minutes we establish Woody’s ordinary world, consisting of Andy’s room. At minute four, we get the story hook: the toys come to life. At this point we’re introduced to the major players: Mr. Potato Head, Slinky-dog, Bo-Peep, etc. Relationships are hinted at and we see that Woody is the leader of this clan. The complexity of this world deepens when the first obstacle is introduced, allowing us to see how Woody normally functions in the ordinary world. The obstacle is Andy’s birthday party and a covert toy-style mission to see if there are any new, bigger and brighter, toys to be worried about. This action reveals the emotional core of the film: every toy’s deepest fear is that they will be replaced and Andy will no longer love them. In the first twelve minutes the film has set up the world, how it works, and what’s at stake.

2) The Call to Action

At minute fourteen, Buzz Lightyear shows up on screen. Something new has arrived to disrupt the ordinary world. This is what the hero’s journey calls the call to adventure. In Toy Story the call isn’t an invitation to a quest, but it is a catalyst that disrupts Woody’s status quo. Woody tells himself that this new toy isn’t going to change anything and we enter…

3) The Refusal of the Call

This is the debate section where Woody tries to keep his authority, but is slowly usurped by Buzz.

4) Crossing the First Threshold

Woody’s refusal culminates when his flaws of pride and jealousy cause him to pick a fight with Buzz. Both toys fall out of the car and Andy’s family drives away, leaving Woody and Buzz on the pavement. The two have now become LOST TOYS! This is the moment when Woody and Buzz cross the first threshold and move us into act two. This is the point of no return. Woody and Buzz are no longer in the ordinary world but the special world, which will force them to grow. The energy of the story changes here because the two have a new desire: to get home.

ACT TWO:

5) Tests, Allies, and Enemies

The next seventeen minutes of the film constitutes the fun and games section where our heroes are presented with tests, allies, and enemies. When I went to film school we called this the “trailer section.” It’s where all the gags and jokes used in a film trailer come from. This is the section of the story that fulfills the promise of your premise. Toy Story’s premise is: how do two rival toys find their way home when lost in the real world? Well, they hitch a ride to pizza planet. They get chosen by The Claw and taken home by the evil neighbor Sid. They defend themselves against cannibal toys. Each obstacle gets harder and harder. And it leads us to…

6) The Mid-Point

In the hero’s journey there isn’t actually a mid-point, but in screenwriting it has become very important story beat. It’s where the energy of the film swings up, or swings down. In Toy Story it swings down. Buzz comes upon a TV commercial selling Buzz Lightyear action figures and realizes he is not the Buzz Lightyear, but actually a TOY!

7) Approaching the In-Most Cave

The mid-point also affects Woody and propels the story into the next section. Woody continues to put out fires while Buzz has his existential crisis. This is known as approaching the in-most cave or continued obstacles and intensification.

8) The In-Most Cave

At minute 57, Woody hits rock bottom and reaches the in-most cave or crisis of the story. Both Woody and Buzz are trapped, Woody’s friends have abandoned him, and he can now see that his pride has led him astray.

ACT THREE:

9) The Final Push

Just after the crisis usually comes a change in fate. Sid takes Buzz into the backyard to blow him up and Woody realizes he must save the only friend he has left. This propels us into act three and the final push where Woody devises a rescue plan.

10) Seizes the Sword

Woody enacts his plan in the climax and seizes the sword by saving Buzz’s life!

11) The Return Home

But the return home is still wrought with tension as Woody and Buzz chase down the moving van. Some consider this a second final climax (think horror films where monsters you thought were dead jump out at the last minute). Woody grows by putting his pride aside and works together with Buzz to reunite with Andy. As the film closes Buzz and Woody have returned to the new ordinary world with the wisdom and friendship of their adventure.

This is classic design used well! It creates an emotionally engaging and well-paced story. If you like this story design I highly suggest reading Sheryl Scarborough’s guest post that continues this discussion in regards to three-act structure.

However, despite popular belief, classic design is not the only way to tell a story. My next post will outline the hidden agenda of arch plot and why we need more storytelling options!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!

I want to thank everyone for reading my Organic Architecture Series! I realize this was a long series with lots of posts. The following are the links to all the different articles. Feel free to bookmark this page for easy reference!